Riptides crash and clutch

onto an exhausted shore–

— a lover apprehends his muse

Riptides crash and clutch

onto an exhausted shore–

— a lover apprehends his muse

In these past few months I have not been as active, there simply hasn’t been enough to write about. However I’ve also been [consciously] working on becoming more reticent and selective of my words, especially with recent events.

I began writing this two days ago before realizing it was the 17th of Tamuz, and had forgotten to fast. Disappointed in myself, I stopped writing. This summarizes how I have felt for the past few months; busy, displaced, erring, and distressed.

I am currently working three part-time jobs in a mad rush to finally pay off student debt and save as much money for Israel as possible, which has been more exhausting than I would care to admit. I am so exhausted that I sleep in on Saturdays, my Shabbat, and often do not make it to synagogue. I do not feel like myself, and I miss home, and these whole final few months have been a challenge to my will and my identity, and most of all, for my patience.

The ongoing process with the Jewish Agency to finalize my Aliyah plans, originally set for February, then July, and now hopefully next month, has brought out my deepest concerns.

I am stubbornly beginning the process of packing, and downsizing, avoiding the full responsibility of being prepared for this move, because I am skating over the possibility of my Aliyah plans being rejected. Due to this prolonged process, I have confirmed with my Aliyah representative that I will remain in the States until August, supplying more time to organize a program placement and strengthen my finances. But my grievances with the Jewish Agency’s lack of transparency or much-needed warranty for seven years of dreaming remain.

The 17th of Tamuz marks the three weeks until the 9th of Av, a notoriously dark day in Jewish history, the greatest of these events being the destruction of the Second Temple by Roman siege in the year 3829 (69 CE). And on this day I fight an ongoing anguish, like a Psalmist lamenting for Jerusalem, so far out of reach. By the end of these three weeks will I hear bad news?

Hesitantly, I understand that despair has, and can, become joy overnight. That with an aggressively positive and disciplined attitude, the busiest schedule, the most tormenting worry, and the greatest obstacles can be overcome with steadfast determination. Private grief can result in unimaginable victories.

While vacationing out West, I walked into Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, astonishing in its sheer size and quantity. I almost became lost in the many floors and labyrinths of stairs and shelves when I found myself in the section-wide Middle East affairs, hundreds of anthologies together; I rebought one of my favorite collective biographies (having given other copies away), Like Dreamers, which tells of the stories of various members of the 66th Battalion (Paratroopers) tasked with retaking the old city of Jerusalem.

Reading the story Chief Intelligence Officer of the Paratroopers, Arik Achmon, I was inspired by his ethic of planning the opening stages of the Six-Day War, while being imbedded in University studies, processing a difficult divorce with his two children, and having virtually no experience in intelligence gathering (Achmon was given officer status by his senior after attending one rushed exercise), to standing on the liberated Temple Mount days later in a battle-weary, sleep-deprived, sore, and grieving state. But on his Hebrew birthday, the steadfast Arik Achmon was able to experience the most coveted opportunity that could not be afforded to Jews in twenty centuries, because of his hard work.

Walking along the placid beaches of Southern California on the final leg of my vacation, the jewel of American luxury, with one of my best friends and his sister, I couldn’t have been further from that present moment.

Looking out to the Pacific with wet sand between my toes, I desired Jerusalem, I wanted and continue to want to be home, to be a part of this history, that Jews in their centuries of fasting on the 17th of Tamuz could finally now realize through their tearful prayers.

I am tired and worried of being in the same constant state of yearning. What could I do with my life that exacts the same yield of passion I’ve had for this mission for the past near-decade?

Nothing. I will have nothing, and in the back of my head sits an unfulfilling library of contingencies.

What has been will be again; what has been done will be done again. There is nothing new under the sun.

I am sinking into the rhythm I had felt around this time a year ago, the damning repetition that drives one mad. But a full work schedule is necessary for the time being. The illusion of being so far from home is, again, a daily reminder of my purpose. Don’t let habit rule you– leave as soon as you can.

As the day of my departure looms, I mull over the years that have led to this season. It is vastly different than I had imagined, but my heart still swells with that comforting anticipation one feels when they dream of their future. I remember the first time I landed in Israel, that citrus breeze rippling through my taxi’s window taking me to my weekend’s stay at a Tel Aviv beachfront hotel; that is almost what I feel now. The elating vindication of being lost in a distant whim.

However, this time is refreshingly different than my second arrival in this past year, during which I felt blasé. I landed knowing I had a mission to learn Hebrew as fast as possible, but in those five months it could only be a taste. I wasn’t there as a citizen. That changes in a matter of weeks.

It is so good to feel that passion begin to resurface, the workings of a long-lasting hope fulfilled. It is the time to give life its proper name.

As I’ve hinted in my previous post, my focus has slackened when I arrived back in the states, and my mentality has been consistently challenged. It threw me into the brutal wake of a depression I’ve been since battling upward.

Each morning that tempts me to sleep in an hour later, I fight; I throw myself on the cheap Ikea rug at my bedside, and immediately begin pounding push-ups without prior stretching. My body stands on stilts above the rug, as I shove encroaching thoughts into a figurative bag.

Everything is meaningle—

Lower. Push.

Is this behavior manic? Maybe? I feel it’s necessary.

I need to prepare, to thrash the chemicals in my head out of order so they can rearrange. I crave discipline, and it is so hard without accountability.

—

One morning while working at the coffee shop, I met a man with a thick Australian accent. I remembered my friend Daniel, currently serving in the Nahal Brigade, and all the stories he’d told me of his upbringing in the land down under. I asked this man where he’s from, he said New South Wales. He pointed out the Star hanging around my neck, and we found our connection.

“I served in an undercover unit in Southern Lebanon.”

“No kidding,” I couldn’t contain my shock, such a small world for Jews! “…when did you serve?”

“While the US were tied up in Desert Storm, and Saddam was launching SCUD’s over Israel. It fucked me man, I’ve been seeing therapists for years. It really fucked me.”

The conversation turned down a somber road, but the enthusiasm in his tone revealed his contagious sense of hope. His upward battle? I fastened a hopper into the La Cimbali and began pulling his espresso.

“What is it you want to do?”

“Tzanchanim.”

“Tzanchanim, and did you have your Tsav Rishon?”

“No, I haven’t made aliyah yet.”

He told me stories of his time serving as a Paratrooper in a branch of Nahal, which admittedly confused me. But these reconnaissance units generally lack jurisdiction; being the best of the best, they are pliable to the army’s will. Wherever they have a use for a special unit, the army finds a way to bend the rules.

“I was deployed so quickly, I didn’t even have time to do my jumps.”

“You didn’t get your wings?”

“Afraid not mate, but I was in and out so quickly it didn’t matter.”

He wrote his name and number on a ripped wedge of newspaper and gave it to me.

“Please call me, I want to help you as much as I can before you leave.”

—

Actions carry varying consequences. Your world could be falling apart around you, and you can sit and map out the origin of each and every blame.

But what of inaction? Wallowing in self-pity and sulking about your day, unloading your problems onto others’ shoulders? Asking why and why again?

Does inaction, too, have a consequence?

The universe is objectively and indiscriminately just. Ze mah she’yaish, it is what it is, deal. You are neither Evil nor Good. You just are. He just is. You may be the most unfortunate soul on the face of the earth, objectively undeserving of every calamity that has befallen you; like Job and worse, this time not bound by the devil’s pact with G-d.

But if you choose to do nothing, the consequence is nothing, and more.

I have believed in this for as long as I can remember. But I feel I haven’t begun living it until now.

This is will.

Regardless of vying conditions, your boots don’t just stand there, they push through the mud.

Chasing after meaningless wind.

Life is a brutal, messy, heart-wrenching trial as much as life is a glory, a journey, an adventure, beautiful and spontaneous and unexpected.

What a disheveled life.

So awful and worthwhile, and it can all end at any corner, at any given moment, as abruptly as when we were once born out of nothing; one of the things I tendentiously love about life. Maybe not the death, but that element of life that keeps it so alive, and vital, and beating, and existing. One day it began, likewise it ends.

I have been in the United States for about a month and a half, and I am enjoying it. Not without its challenges, being back in the States has been a test for my final self waiting to be absorbed into the place I call home six-thousand miles away.

I turned twenty-four in June, and already feeling a great deal older than the people I lived with during those months of Ulpan, or Hebrew immersion school, I’ve begun to deliberate what I want versus what I need, versus what I must do: All fighting inside me at once every day.

Four months away and I will be back in the ancient rain-laced preserve of an Israeli winter. I am deciding on whether I will be taking one final Ulpan before the Army in August, or an expedited program so I may draft by April. I want to choose the latter, but realistically I must wait to consult with the immigration representative I meet with next month.

It has been a season of closures since I’ve arrived back in the United States, and a supply of conflicting emotions have catalyzed within. Losing my family’s young dog to an aggressive disease and my father’s car I’ve held privy for its sentimental value and making final goodbyes with certain friends, altogether have really closed a chapter on this American life for the time being.

Who knows what happens next?

I am ready to return. I miss the night marches with a rabble of voices yelling out in volition their determination to hold onto the land. I miss the surge and crash of Mediterranean water on my legs and chest, the rare sight of lightning that illuminated the ragged teeth of Mount Carmel, the beating rays of the midday sun and the purple skies of midnight. I long for the night fires in the wilderness with the hevreh drinking to the point that vocalized commitments came out: I will take a bullet for you, and I promise to attend your beret ceremony, G-d forbid.

A concern I’ve slowly begun to scratch the surface of is my coming of age and the responsibilities and steps that traditionally join it. There are women in my life, but not a single desire within me to settle. There are friends beginning families, but I cannot start a family right now. And the pressure is heavy and real.

I have family here in the States, and family in Israel. So in a sense I suppose I am starting a family. And for now Israel is my wife, and I don’t believe we’re divorcing any time soon.

I stare down my path with sober eyes, in its truest, naked, starkest form. After our Sh’ma we lace up and take life head-on, every morning, every day.

I am going to wear those coveted red boots and I need all the strength and focus I can release right now so that I earn them.

Tokef v’moked.

“I’ll be going to Layla Lavan.”

“Jesus, going straight into Layla Lavan? You haven’t worked with these guys before?”

“I can’t, you know? With Ulpan and work.”

“I get it, your schedule is full.”

“I mean, I’ve been training everyday, sometimes with friends and most times solo, working myself as much as I can.”

“You’ll be fine, it’s just-”

“It’ll be a baptism by fire.”

“Yes, exactly.”

“Is it difficult? ” I asked, knowing just how unnecessary the question was, but wanting to get as real of an answer as I could.

“Layla Lavan (white night), or tironut (training) in general?”

“Tironut.”

“It’s extreme, but do you know how to keep on?”

“Mental.”

“Yes, exactly. Shoot for as high as you can. The training is a bitch, but listen Nachshon, it’s worth it. In kravi what you’ll be doing for majority of the time is holding a part of the border. The days are long, but you do jack. Nothing. The only part you need worry about getting through is tironut. If you can survive tironut, it’s cake. It’s so good and rewarding. The army rewards hard work. You even go home on Thursdays for an extended shabbat.”

“B’emet?”

“Really. Go to the beach, have dinner with your family, fuck your girlfriend, whatever. Get back to the grind on Yom Rishon and repeat for seven months until you’re combat ready.”

He pulls a video up on his phone; a rabble of olive-drab warriors in boonie hats standing before wet earth caked in mud.

“Achat shteim shalosh!”

The soldiers jump forward and smack prone in the mud, their elbows and knees jerking forward in the thick, sinking ground, rifles held above the clay.

“Is that a Galil?”

“Negev.”

I continued to watch in awe as the full-gear heavyweights confidently pushed their way through such hampering obstacles like tanks on asphalt.

“…During war week, you’ll sleep every other day. Not much, two hours tops, but your body is going to soak up as much rest as possible. During the days, the m’faked will hand out maps with topography and shit on them.”

“Okay.”

“You’re going to go through hellish marches, and will be expected to always stay on alert. If a time comes where the group stops, there is no sitting. You kneel with your rifle in your arms. But after these little missions are finished, you’re going to want to lay around. Don’t. Study the maps as much as you can. By the end of the day, the m’faked will send you out and you need to know exactly how to get back to base. …But honestly, during most marches, you’re expected to carry your rifle at your shoulder at all times, you know, ready to shoot.”

“Yeah.”

“But, much of the time I’m walking with my arms tucked in my pockets. That’s not how it is in a real combat situation. You’ll know and feel the difference. Last week, we were moving through a Palestinian village looking to arrest a man who was selling weapons. We couldn’t find him all night, but we had other suspects.”

“Yeah?”

“Do you know what we found? In one suspect’s house, business cards tucked in a stand belonging to a journalist.”

“Is that who took the photo?”

“Yes. At about five AM we were leaving the village, and ahead of us a man was on the ground setting up a tripod. That is why we wear the masks.”

“To protect your identity.”

“Exactly. You cannot touch them, bother them, destroy their camera, by law. You just ignore them and move on. …I’m in the photograph somewhere. Don’t remember where I was. See the guy with his hand over his eyes?”

“Is that you?”

“No, don’t think so. But he’s hiding, you don’t want to be too familiar in the West Bank.”

“It looks difficult. Exhausting. But this was my intention all along. And I’ve always doubted myself, my poor Hebrew, my body, my upbringing.”

“That will all fade soon. I can already tell that you’re one of us, you’re a brother. Honestly, don’t doubt yourself.”

That changed when I came here. Do I have fear? Yes I do. Not of the physical challenges, not of the gibush. I fear for losing myself, who I am in the place I came to find who I am. I made this clear to my American-Israeli friend as we nursed Macabi Beer while pounding shots of whiskey and rolling cigarettes; he called me brother.

The humid night brought in a hazy smog which cradled itself in the Jezreel Valley, likely from the ammonia plant east of Haifa. It fortified the deep feeling of strangeness, one of life’s inevitable turns that leave permanent marks on the always-changing, pliable human conscious. The alcohol wears off in the middle of the night as I lay, looking out the iron-paned blinds of my bomb-proof window, as the haze dissipates and the sun burns the dark away.

Ghosts and unwelcome memories linger, I feel I look down on them from a lonely mountain’s crest. But it is a another day, another chance, a new time under the sun to fulfill the unforgiven minute with sixty seconds-worth distance run.

(Anachronistic thoughts from this past week gathered in a single entry)

An aqueduct’s silhouette, like an ancient arched wraith, rises from the shadowed valley along bus route 480. Unpleasant odors fill the stale air, relieved by an open window above my head bringing in torrents of fresh wind.

We cruise fine and fast, when suddenly there is stalling traffic, and the encounter of bright blue lights in the opposing lane.

Highway One. 20:27. Outskirts of Jerusalem.

I hear the marriage of laughs and children’s shrill cries while Gotye wails over them all. Dim lights keep the cabin lit; too tranquil for the man in the seat next to me, who has fallen victim to sleep.

The strange outlines of beautifully endowed hills and mountains are highlighted under the purple sky and amber clouds grazing above and beyond. The massive grotto of a contoured cliff appears beside the freeway, littered with occasional markers and plaques and monuments; the Palmach fought on this hill in 1948, the Ottomans erected a citadel here, Hadrian raised a wall there.

—

On some days, like today, I feel like I can’t hold on. A friend had sat next to me one evening and told me “you are the most serious person I’ve ever met.” I don’t know if I can take her words as a compliment or a validation for the foreign nature of my soul’s fabric. I think too much, I have known this. I curse myself too often for it.

Jerusalem’s golden glow can be seen in the night, from the foundation of Mevaseret Tzion’s unexpectedly winding hills. Climbing to the plateau, the bus stops at Harel station, as a number of smiling faces and families anticipating Yom Tov disappear into the night.

A couple relocates in the seats in front of me. She wraps her hands around his neck, kisses him on the cheek and presses her lips into his ear. The streets below are uniquely quiet per the normal busy Jerusalem scenery; many have fled to the Kinneret (Galilee) for Passover. Feelings conflict within me. A breath of supernatural peace washes through my busy head and eases my heart. My heart would be the man arguing “it is too windy“. An infamous hazard for every human being, regardless of age.

The bus enters the garage of Central Bus Station as the crowd erupts in activity, as though we are on a plane that has just landed. Phones and conversations suddenly alive with the lights that flicker on.

A man in tan air force uniform stands in the aisle. Behind him, a man in dress clothes and tzitzit impatiently gathers his kids. A glock is holstered on his belt.

I’ve landed again.

—

My future I am tossing to the wind. I have made my decisions, and now I am working a plan post-IDF. Where am I being called to next? What is in my heart that I can give to the world? I am sowing my seeds here, where and how can they bloom?

I’m stifled. I’ve been stifled all my adult life, feeling unable to bloom!

I am returning to a thought that I will eventually move northwest. The mountains and trees of Washington and Oregon, the raging waters of the Pacific, the cold rain and commanding nature and tender, pale, warmly gratifying sun I equate to the region, in my memories and stays, I believe will be a good season of rest for me; deep down, I hope it gives me a chance to gather the pieces of my salvaged faith.

I run my hands along the wailing wall and bow my head; a plain-clothed Masorti thumb on the hands of black-coated Haredim. I whisper a few private petitions, gather my pledges and promise myself and Whomever is listening that I will not give up, ask for the necessary strength to carry through, and walk away. Jerusalem at night feels near freezing in a t-shirt; having been 30C in Haifa earlier today, it must be no warmer than 18C now. I covet a silk scarf a man wraps around his whole upper body

I ride the light rail back and forth across the city, waiting for a hostel to reach back to me. I refresh my phone and open an email which reads:

“Dear Brendan,

Since we do not recognize ‘conservative conversions’, we are unable to host you.

Shalom”

It is my first encounter with the ongoing strife between movements that make us all uniquely Jewish. The news stings, but does not deter me. How could it?

I would be murdering my identity if I were to give up. That is not the fabric of this soul, most serious.

—

A newer friend of mine returns to the kibbutz from basic training for the weekend. I only know him as Ari, his real name unknown. Perhaps he legally changed it after his conversion somewhere on the East Coast.

Standing a foot taller than me in black boots and a ruffled green General Corps uniform, himself hoping to graduate into the cobalt and black of Magav (Border Police), Ari comes from a nearly identical process of converting to Conservative Judaism, having dealt with the issue of recognition with subterfuge. I tell him of my encounter with rejection.

“What did they say when you told the Jewish Agency that you are a convert?”

“You don’t tell them.”

And here he is, he made it, albeit with plans to formally convert to Modern Orthodoxy while in the army.

These experiences have raised so many questions within, mostly regarding the state of my commitment. I love this land, and the choices I have made. I know who I am, but with this I know what I have come to hate.

Legalities and lies.

I am sorry for not writing in a while, I would not be lying if I told you that this is the most difficult thing I have ever done.

Besides the long mornings losing myself again and again in the lessons of an alien language that takes me try and try again in order to remotely understand, the repetitive work here in a collective of cold-shouldered kibbutzniks, a temporary stereotype I’ve learned and prepared myself for when I landed here a little over a month ago, and the occasional, stifling loneliness, there is one true preparation I have set my focus on: Tzanchanim (the paratroopers).

I’ve since joined a group of young guys led by a man who has experience training alongside Yahalom sappers (the commando unit responsible for detonating the terrorist network tunnels in Gaza two summers ago) and has completed a gibush, a gruesome “tryout” required to access elite units in the IDF.

Every other evening I end with black nails packed with dirt, peeling knuckles cratered from stones; thorns and bristles chalked across my back and chest, skinned elbows, bloody knees, bruised lungs. The mornings are a routine struggle to raise my arms to wash my own face. I am fighting sicknesses once a week. The raw stress tempts me to quit; but that is exactly what this training is trying to do to me. Kicks in the groin while planking, pepper spray to the eyes before going for a few brief sprints, being dragged backward by my comrades a dozen meters over rocks and tree roots on a final army crawl to finish an exercise. It is all worth it.

In between planks on aggregate concrete and sprints in the scorching April sun, a tan UH-60 circled above our heads with a tough whir. There’s our boys, I thought, with sweat pouring into our open mouths, as salty and dehydrated as rawhide.

You want to join them? our group leader said. Quit being a fucking pussy and get on your knuckles.

—

I have decided that I will end my temporary stay here with a mock gibush, governed by members of elite units in the army. This is more than necessary for access into Tzanchanim, but I will prove to myself that I am capable of joining a tougher unit if the opportunity arises. After I return to the United States in August, the six month countdown to Aliyah begins.

I am broken, and it fucking sucks, but so be it. That is how this miracle state came into existence and will continue on the shoulders of a chosen people strong enough to keep it alive.

I love my people, and the promise of this beautiful land too much to not stop.

I’ve loved you

until the moment you were

taken from my rib

My sides are still sore from the ripping and the mending;

I’ve remembered you

standing on the color-absent sleeping shore:

exhaling that intoxicating purple haze

escaping the ruins of wars, wars, wars

that the schlepper generation we are called

still wearily participates;

I’ve felt you

sitting shiva times seventy

from the pale arms of winter’s sunlight

to the kindled retreat of

hot milk and cocoa beans,

you in your flower dress, Tillamook green

woolly arms contently rest on frayed schwarz leather

why, why, why

did I look away to the busy Sunday streets

mulling another absence too early, panicking, [hostilely]

–helplessly captive in my lonely mind’s eye

kilos from your embracing dainty hands

forgetting to savor the moment

and my lukewarm café?

MOSES DISTANCES himself from the throngs of Hebrews gathering on the shore while he begins an uncertain conversation in the Holy Presence.

During the wait, the Chieftan of Judah feels the shifty waters of the intimidating Sea of Reeds on his feet. His tribe gathers behind him, vulnerable, mortal, panicked; his spiritual and martial commander arguing with G-d even at this vital moment, the faint contour of Moses’ staff angrily waving in the air toward a rageful sky, from where in the distance a stanchion of flames stretches downward; the uncomfortably close thin line epitomizing the nearness of a vengeful Egyptian cavalry to nomadic, fragile life.

I choose You to choose me.

The Chieftan silently, impulsively, hurls his body into the waters. The motherly screams of women on the shore, the silence of disbelief overtaking a once boisterous, stormy crowd, and the shouts of a few indecisive men erupt. The dark waves of the Sea of Reeds pulls at the Chieftan’s robes as he sinks lower beneath the burning salt lido churning around him. The deep, black indigo bathes his chest, his neck, his nose and ears, until he is gone.

—

I reach out my hands along the Mikvah’s walls to keep my naked body submerged. Resurface. Too hasty I think to myself while the Beit Din, the House of Judgement consisting of my Rabbi, my synagogue’s cantor, and its director, stands waiting for me to immerse again.

The warm water softly beckons on my shoulders and breasts. Going under again, flare of the nostrils, assault on the eyes, the lifting pressure in my head, and… peace. The change. The transformation, the will actualized by the commitment of my heart.

Years of desire and shouting out, I choose You to choose me.

Resurface.

“One more time” I hear my Rabbi softly speak.

I remember the long road that has led upward to this moment. The questioning, the depression, the confusion, the anger, the tears… the silent glimpses of joy like sunlight grinning through cloud shade.

I remember asking myself who the fuck am I, walking dozens of miles from my parents’ home in the middle of night, feet soaked in slush and snow, wondering about the state of my soul after a shouting match with my parents in which I had cursed them with colorful insults and slammed my boots on the floor.

I remember the comfort of a woman holding my hand with a glass of wine in the other, asking me why, then warning me, warning me until my eyes could no longer comfortably look at hers, and finally, not surrendering, not breaking, she began to console me with intoxicating words of how she has not opted from the faith, that we are a tribe, that I am taking on an ancient and heavy commitment, that I cannot opt out either.

I remember the shame of pulling out my active phone during a communal gathering of singing during a Shabbat service in a soldiers’ hostel in Tel Aviv, a gross violation of the Shabbat laws, that caught the attention of a young reservist with leathery skin and a knitted kippah. He eyed me with a sort of stare nixing a brief shock and disdain with an understanding that whispered it is okay, he will get there one day.

I remember forgetting how to pray, and learning again, because of my primitive understanding of Hebrew, and having always prayed to Jesus, until the revelation came one night in 2011 while gazing into the maze of Chicago’s skyscrapers from a hotel room, going through a messy breakup, that I need to stop worshipping a man and my crumbling relationship; that evening I found a sliver of G-d, reaching down into the cold ruins of my consciousness from the starry lights of the many windows, like glimpses of warmth in the sea of black concrete during a chilly downtown night:

Shema Israel Ad-nai Eloheinu, Ad-nai Echad.

was the first prayer I had prayed, battling a massive headache, strangling loneliness, questioning my future and my willingness to stay alive for it.

—

“Stretch out your hand, Moishe.”

The words penetrate the chosen leader’s focus as the clouds grow darker, a harbinger for night.

Wood smacks stone. The waters flee in furor, light obliterating darkness. Two majestic curtains of sea stretch into the brewing clouds, opening a passage for the Hebrews. The nearly-drowned Chieftan is regaining composure, having been swept under his feet by the power of the parting.

The Hebrews start forward, abandoning carts and deadweight, led by an astonished Moses and Aaron. Trembling with fear, awed in the Presence.

The Chieftan is named Nachshon, son of Aminadav and directly descended from Judah, son of Jacob. His namesake, allusive to the Hebrew word nachshol, “waves”, is the name I am taking on as a Jew.

Reading from a framed prayer, in Hebrew, at the poolside, wet hair covering my eyes from the third immersion in the mikvah, I begin:

Blessed are You, Ad-nai

Ruler of the Universe

Who has sanctified us with the mitzvot

and has commanded us concerning immersion.

My Rabbi begins a beautiful Hebrew prayer, the most beautiful prayer, and I hear him speak my name as though it were written in a book. My identity rose out of the water that day. My desire, my current life, and my future, family, children, home, I will go with G-d and mend the world in an everlasting covenant; I will speak of these words to my children, speak of these words while I sit at home, when I walk along the way, and when I lie down and rise up. I will bind these as a sign upon my hands, between my eyes. I will hang them on my doorposts and upon my gates.

The waters are open, blown back by a strong Eastern wind; my life’s Egypt behind. I am free. I belong. And the journey has only begun… although I am still imperfect, although I still, like a child, continue to learn from misunderstandings and petty mistakes, I am untouched by regret, rather, yolked by delight that I am going where I am meant to go.

And it has not been effortless, this choice will not be without complication. My identity was once scarred by a controlling, aggressive darkness, unconfident and insecure. Difficulties in the road ahead are surely waiting for me. The future is uncertain for all of us, no matter where we are in life.

Stretch out your hand, Moishe, take a breath, go with faith.

Go.

SHOMRON 18 TISHREI 5776 – SAMARIA, 1 OCTOBER 2015

A white Subaru hatchback drives over the pacifying sound of gravel as it slows to a stop, making a turn onto another winding road to reach Highway 60, toward the Neria settlement in the west. The driver and the front passenger, Eitam and Na’ama Henkin, are returning from a class reunion as their four children in the backseats begin to quietly wink off to the scenery of somnolent hills in Samaria, from where the sun had cast its final honeyed light hours earlier.

Another vehicle suddenly unsheathes itself from the camouflaging dark, driving into the lit intersection, blocking the passage of the Henkins. Two men jump out from the doors, masked in balaclavas, and fire their small arms into the front windows of the Subaru.

The children’s silence is likely what spares them from further gunfire; the eldest, nine year-old Matan Henkin, takes control and urges his younger siblings to be silent as he watches his parents’ bodies rip apart by the sudden hail of bullets. Just as quickly as the attack began, it was over; the critical silence and quiet murmuring of confused children grotesquely steals away the normalcy of a family returning home, on holiday, with no expectation of what violent execution has just taken place.

Minutes later, the children now flashing brights and honking on the horn for attention, an off-duty medic and soldier arrives at the strange scene. The soldier immediately whips out his M-16 and checks the shadowed hills for any signs of terrorists. The medic, Tzvi Goren, is horrified to find that behind the blood-stained doors, two limp bodies sit placid while children scream and panic in the backseats; the youngest, a four month-old, cries unconsolably while bound in a carrier.

Tzvi’s worst fears, while examining and comforting the children, realizes they are now orphans; he brokenly attempts to follow procedure, averting the traumatized youth’s attention from their parents, while waiting for the army to come.

A day later, Matan reads mourner’s Kaddish for his parents over the wailing of friends and family, an intrepid voice among a sea of people with no comfort, wounds raw, still searching for the faintest glimmer of hope in a stifling valley of shadows. The two well-known, well-loved parents, who made Aliyah from the United States, are escorted to their final resting place before Shabbat begins, thousands of mourners in attendance. The attacks that orphaned the four children are but the beginning of a wave of attacks that will claim the lives of two more Israelis, and injure dozens more, with no end in immediate sight.

—

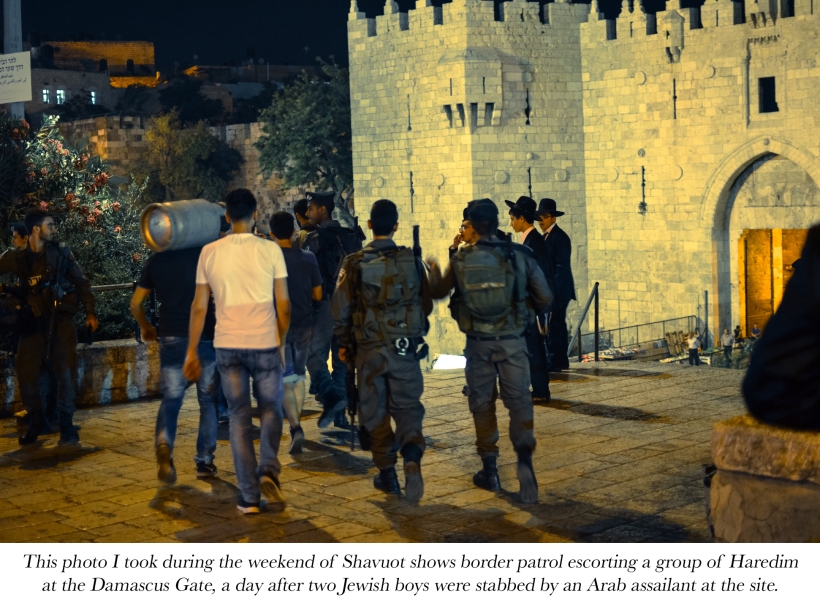

HA’IR HA’ATIKAH 20 TISHREI 5776 – THE OLD CITY, 3 OCTOBER 2015

Among the crowds inside the Lion’s Gate, a Palestinian law student makes his way through the throngs of prayer gatherers and tourists on this often-troubled road in the Old City, locked between the Arab quarter and Temple Mount.

In recent weeks, this site has been a nest of trouble between Arab dwellers on the Temple Mount and Jewish worshippers observing Rosh HaShanah; the local Arabs, carrying the perception that the Mount from where sits their Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa mosques, are under threat by the recent large pilgrimage of Jews. Because of this, the Arab masses have been actively rioting from the Mount by use of lethal stones and firebombs, even a failed grenade, on the unarmed worshippers.

Due to this escalation, the Israeli border patrol division of the IDF, unique for their grey uniforms and black combat equipment contrary to standard olive green dress, have been deployed on high alert.

The nineteen year-old Arab law student, Al Bireh, weaves in between the crowds of worshippers sauntering their way to the Western Wall as he lays eyes on his target: a married orthodox couple carrying with them an infant. With a few quick swings, he fatally stabs the father, Rabbi Nehemia Lavie, while severely injuring the Rabbi’s wife and daughter. The crowds of people begin to flee through the narrow streets as the fourth victim, IDF reservist Aharon Benita, is mortally wounded and his rifle confiscated. The terrorist then begins to fire wildly, vainly, into the fleeing crowd before he is almost immediately neutralized by a Border Patrol officer.

All of these acts occurring in unusual unison surround the bold announcement last Wednesday of President of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, in front of a cheering United Nations General Assembly, that the Palestinian people “will no longer continue to be bound” to the 1993 Oslo Accords, a failed attempt at mutual recognition by Israel and Palestine, laying grounds for Palestinian statehood, and peace.

I remember watching the televised speech, in shock, followed by the raising of the Palestinian flag at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City. I was not in shock because of the lack of desire for a consolidated peace between Israel and Palestine, not because I do not believe that Palestinians have the very basic human rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, nor because I do not believe that Palestinians should have access to the founding of their own sovereign state.

But under these threats? These conditions?

The chilling voice of a woman buzzes on my phone, tzeva adom, tzeva adom, tzeva adom… “code red, code red, code red”… At that moment, an untamed rocket was screaming into the night sky, bound to strike down on Israeli soil.

This warning system, found on smartphones, is designed for Israelis in the event of these frequent, often unpredictable launches. If a rocket is tracked in the airspace over a specific town, its residents will receive a personal alert; being abroad, I can receive alerts for any region under fire.

The weight of the situation has prompted a lot of personal thoughts, especially as I plan to make this beautiful, complex country my home in the next year. What can prevent further attacks on my people? What measures do we need to take as a collective, as a fighting force? My motto breathes deep, interminable, defend life. Defend the life of my people, defend their rights, their happiness, defend the youth until they are ready to live under the helmet and carry the flame of that mantra.

But when will defense become depravity? Deterrence, the long-embraced strategy of the IDF, is condemned by the world. I have always believed that it is necessary to discourage terrorism, by means of the home demolitions, the night arrests, the brutally long prison sentences for convicted terrorists… who can complain about demolished homes, an active, violent convict being stolen away in the night, and living in custody, when we have to bury our mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, sons and daughters? These strategies, in spite of repeated acts of terror and inevitably uncontrollable violence, has been effective in keeping Israel safe. But is deterrence effective in solving the Palestinian problem?

—

The stabbing sprees are becoming wildfire. From last weekend, a mounting figure of incidents are spreading from the West Bank, to Jerusalem; whose mayor, Nir Barkat, has just urged its citizens to carry firearms; and in the last day, to Tel Aviv and Yaffa.

Today in Israel, a list of incidents grow:

05:00 Men throw stones at a bus near Um al-Fahm

11:56 Rocks are thrown at a car driving past Afula

12:19 A Haredi man is stabbed and seriously injured in Jerusalem, his assailant shot and killed

13:02 Palestinians throw stones at vehicles passing Gush Etzion

13:22 Palestinians throw rocks at non-governmental organization vehicles near Halhul

15:00 A terrorist stabs five people with a screwdriver in Tel Aviv, and is killed

15:28 A glass bottle is thrown at a passerby in Jerusalem

15:54 A young man is seriously injured in a stabbing near Hebron

17:15 A soldier is lightly wounded by stones during a protest in Halamish

17:20 A Palestinian minister is wounded after stones are thrown at a vehicle passing Nablus

18:20 A Palestinian is killed and 9 police officers are wounded in clashes at Shuafat refugee camp

19:06 A soldier is critically wounded in a stabbing in Afula

The situation’s urgency mirrors a minor Intifada, a Shaking, an uprising, and various newspapers and journalists are assessing the beginning of the third such uprising.

As these acts unfold, six-thousand miles away, I urgently watch and wish I were not so helpless. I want to be there now, protecting my country and my people.

But this time is also a reflection, a spiritual question I need to mold into an answer; Defense, Deterrence, Depravity. I cannot stoop to savagery; I need to guard my heart. And at the same time, lives are being lost, and I need to defend life, a priority I hold over my conflict and muse.

The gray skies of this Minnesota autumn are quiet, soothing, maddening; life here in Minneapolis passes with a simple fury and joy, making infant steps toward its true manifestation in the gloriously bright Tel Aviv, where people appreciated life with every step, every waking breath, because we had no choice, because the present day could be our last, because we have a history that did not have to spare us, because we don’t have to be here, and we are; I wonder how I could not only preserve this deep appreciation for free Jews in our Holy Land, but for our Palestinian neighbors, who, despite their negative and often hostile perception of us, are facing a crisis deeper than any act of knife-wielding viciousness could bring about; with our army on the high-guard, it is inevitable that they should act when enough is finally enough, and no one really wants to acknowledge what will happen next.

I ask you, reader, to pray for the Peace of Yerushalayim, for its precious namesake, for those who are dying in her, and for those who endanger their own people from within her.

I refuse to believe that this is how it will end.